Researchers Work to Improve Solutions for One of Physics ‘Last Unsolved Problems’

February 6, 2016

Most people are familiar with the word turbulence, defined as “a fluid state that is random or unsteady,” because of their unforgettable experiences with it. Those who have racked up a lot of sky miles, and those who have not, describe similar experiences of gripping chair armrests and becoming semi-paralyzed in seats when an airliner suddenly drops altitude when flying through choppy air. Thanks to researchers like the computational turbulence modeling team at the Center for Advanced Vehicular Systems, airliners are built to withstand substantial amounts of turbulence. As a result of years of refining the computational models that simulate turbulence effects on structures, aircraft are designed to endure greater amounts of pressure, and the turbulent dynamics of aggressively maneuvering the plane when recovering from it. Although the designs of these air transportation vehicles are safe, according to Keith Walters, an associate director of CAVS, there is always room to improve the computational models that simulate turbulence around all moving things in order to make them safer and more cost effective.

“It is difficult to predict the flow of fluids, including gases, liquids and even some plasmas through computer simulations, because you have to account for all the intertwined, swirling, apparently random dynamics,” Walters said. “That is why Richard Feynman, the Nobel Prize winning physicist, called it, ‘The most important unsolved problem of classical physics.’”

And it is why the Clay Mathematics Institute refers to it as one of seven Millennium Problems and offers $1 million dollars to anyone who can provide a purely mathematical solution.

Shanti Bhushan, assistant professor of mechanical engineering and a CAVS faculty member states, “It’s unlikely that anyone will win that $1million because some of the most brilliant physicists and mathematicians have attacked and are attacking this problem of fluid turbulence. It’s recognized as being really one of the last great unsolved problems. Some of these models are very good, and some are better than others, but our work really boils down to making the current models better but still relatively easy to use.”

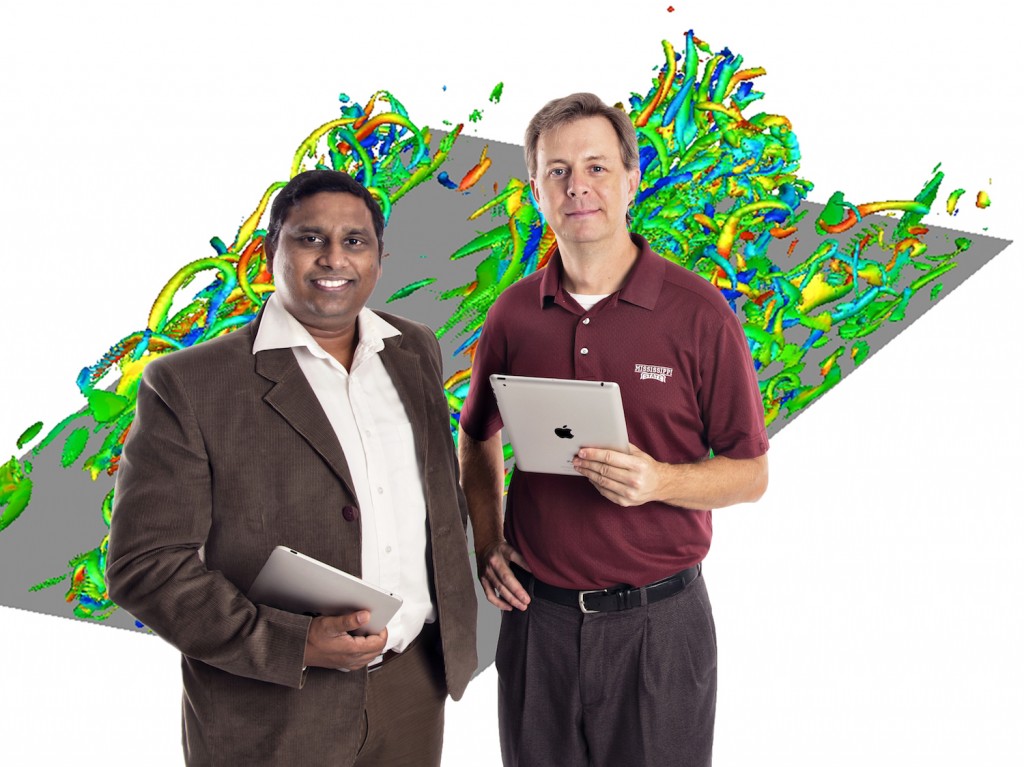

Walters and Bhushan’s turbulence research team is working on a project with the Engineering and Research Development Center in Vicksburg, Mississippi, to significantly improve a turbulence model that applies to ground, air and marine vehicles.

“Turbulence generation for each one of these vehicle types is very different, but we want to create one reliable model that will apply and make accurate turbulence predictions for all of them,” Bhushan explained.

Over the years researchers have created hundreds of turbulence models and one of the challenges is choosing the model that is best for each type of vehicle.

“We talk about generalization because if you’re designing a car you don’t want the burden of having to pick from hundreds of models to determine which one is best for a truck and which is best for a limousine.” Walters further clarified, “We want to be able to say this is a general purpose turbulence model that we can take to the Navy, Air Force, Army, NASA or whomever and say this works really well for all vehicle turbulence scenarios.”

Working with Edward Luke, a computer science professor and researcher, the CAVS team is developing a new approach to model turbulence. Originally funded by NASA, they have implemented this innovative approach into a number of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) codes including the Loci-CHEM code that was developed at MSU by Dr. Luke. The CFD code and turbulence model are being tested by NASA and Department of Defense users as a new method to model their air and space vehicle simulations.

“After we developed the model for NASA, Argonne National Laboratory and the Office of Naval Research expressed an interest as well, and that additional funding has helped us further refine and test it for different types of flows such as marine vehicles or nuclear reactor cooling,” Walters said.

The research team was also recently awarded additional funding through the DoD High Performance Computing Modernization program, in partnership with ATA Engineering, Inc. and the Air Force Research Laboratory. The new project is based largely on attacking issues with high-speed aircraft that are of interest to the Air Force.

“Roger King, director of ICRES, has been extremely supportive of our work, both in terms of finding opportunities and providing material support,” Walters added. “CAVS provides us with the environment to collaborate with researchers with a variety of backgrounds, such as David Thompson an endowed professor in aerospace engineering; Greg Burgreen, a CAVS associate research professor; Edward Luke, professor in computer science; and Adrian Sescu, assistant professor in aerospace engineering.”

Fluid turbulence is prevalent in an incredibly wide array of engineering and natural systems—that is the breadth of impact. Turbulence is critical to understanding how fuel is burned in an engine, how air flows around cars and planes, or how weather patterns form and change. Consequently, millions if not billions of dollars could be saved if researchers can improve the ability to accurately model turbulence.

Bhushan explained the ‘big picture’ impact of the research, “In the long term if you refine one model, so that designers can design aircraft that save gasoline—then tickets are less expensive; or if you use it to improve nuclear reactor cooling systems—then power becomes cheaper; or to improve moving machines that optimize food processing systems—then ultimately the impact is actually helping consumers save money on goods and services.”

Photo by Beth Wynn / © Mississippi State University